A Look at the Odalisque

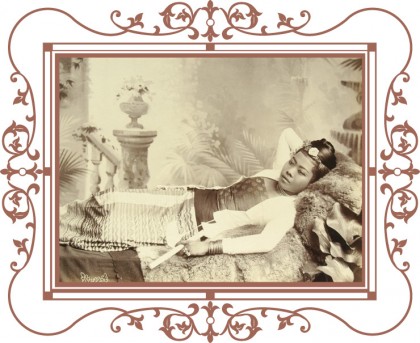

An interesting and important aspect of early photography is the way photographers in South Asia and elsewhere engaged imagery from historical paintings. In Allegory and Illusion this can be seen in the haunting image of a Burmese woman reclining in a pose associated with the odalisque (or concubine). This theme became a popular subject of Western art in 1814 with the painting Grande Odalisque by the French painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. The form of the odalisque became associated with Orientalism, a style that offered a Western conception of the East and implied Europe’s domination of the Middle East and Asia. In the Burmese photograph the woman is posed as an odalisque—though we don’t know if she was a concubine—and is holding a Burmese cigar (cheroot) in her hand. The cigar is significant as it asserts the specific locale of the work, and it also certainly has a phallic connotation, connecting the photograph to the original implication of the odalisque.

In selecting works for the exhibition, I was particularly struck by the historical resonance of this image and became even more enchanted with it during a recent trip to Paris. In between preparations for an upcoming exhibition at the Rubin Museum, I had the chance to visit the Centre Pomipidou in Paris, where there was a small exhibition dedicated to modern and contemporary representations of the odalisque. I want to point out one mixed media work from that exhibition here to show the elasticity of the form and idea of the odalisque and also to show how recently and widely it has been deployed. It is fascinating how the Pop portrait painting Made in Japan—La Grande Odalisque (1964) by the French artist Martial Raysse (b. 1936) refers to the face of Ingres’s odalisque but highlights more of her face, here missing an eye and thus appearing unnatural.